Integrative Medicine & Health Sciences Program Celebrates 20 Years of Innovation

Twenty years after its first graduation, the Georgetown University Master’s in Integrative Medicine & Health Sciences (IMHS) still plays a unique role in biomedical education. The program applies a scientific perspective to health practices outside the mainstream of biomedicine: acupuncture, massage, herbal medicine, mind-body interactions, and others that are popular around the world but understudied by academics.

On the eve of 2024 Commencement, IMHS celebrated its 20th anniversary with a spirited reunion of students, alumni, faculty, and family members. The diversity and impact of the IMHS community were on display as alumni reflected on their experience in the program and shared stories from their work in oncology, anesthesiology, dermatology, acupuncture, architecture, law and more – all informed by the perspectives and critical thinking skills they gained as students.

“The favorite part of the program for me is seeing those students be successful and have a positive impact, to see them reaching their goals and following their passion,” said IMHS Director Hakima Amri. “My aim and that of all our faculty is to provide them with resources they need to attain their goals.”

Rebecca Berkson (’07) addresses attendees.

Rebecca Berkson (‘07) counseled the attendees at the anniversary celebration to “find what gives spark to your life.” For Berkson, her career as an acupuncturist stems from her IMHS studies: She learned about the practice and met her current employer through the program. Today, she visits IMHS classes to teach about acupuncture and traditional Chinese medicine.

“It was a full-circle moment reconnecting with faculty, students, and other alumni,” Berkson wrote in an email. “Hearing how others have used their degree and their unique contributions was not only interesting but a source of pride.”

Shannon McDonnell (right) and fellow student leaders announce superlative awards.

IMHS student and anniversary event co-organizer Shannon McDonnell, who joined the program after working as an emergency room nurse, said the alumni were an inspiration to her as she now considers her own future.

“It really puts so much hope in my heart that whatever I do after this, there’s going to be a way I can apply integrative medicine to it,” she said. As a nurse, she “realized there’s just so many things that were lacking in the health care system that we need, and I think integrative medicine can bring a lot of things into that.”

“Many of the students that come to this program aren’t sure what they want to do,” said IMHS Co-Director Aviad Haramati. “This is a way for them to begin to explore that by being exposed to areas that they may not be aware of. At the end of the day, I think students make better choices about the career paths that they do pick.”

A New Kind of Program

From the beginning, the IMHS program fostered a goal of enriching the medical field by taking an evidence-based approach to health practices from around the world.

Amri herself hails from Algeria, where she finished college before completing her doctoral studies in France. In the mid-1990s she was a Georgetown postdoc studying the mechanism of action of ginkgo biloba, a popular plant in traditional Chinese medicine, when she tuned in to the academic discussion of the nascent field then known as complementary and alternative medicine.

IMHS Director Hakima Amri speaks during the anniversary event.

“My first reaction was like, ‘Why is everybody talking about alternative medical practices in a negative way?’” she recalled. “Because I’m coming from the Mediterranean where we have a high biodiversity, we have our plants endemic to the region that people are using for everyday culinary purposes as well as for treating ailments … but here [in the United States] the medical establishment is undervaluing and underestimating the cultural wisdom that derived from the teachings of Hippocrates and Avicenna underlying their use.”

Amri saw a disconnect between complementary and alternative medicine’s academic reputation and its global significance. The World Health Organization estimates that around 80% of people use traditional medicine, and about 40% of pharmaceutical products “draw from nature and traditional knowledge.”

Amri told her boss at the Georgetown lab: “I think we can teach this.”

“Integrative medicine is practiced everywhere else in the world, and I’m coming from a country where it’s part of the culture, it’s part of everyday life, and here [at Georgetown] I’m studying it in a lab using modern biomedical research methodology,” she said. “I think I can be the bridge bringing these two worlds together.”

She started out by teaching the public about complementary and alternative medicine at Georgetown’s 1999 Mini-Medical School, a lecture series open to the D.C. community.

Dr. Amri (left), an IMHS student and Dr. Haramati.

Around the same time, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) was ramping up its interest in the field, and issued a request for proposals to develop curricular content in complementary and integrative medicine at medical and nursing schools. Amri saw an opportunity to develop her Mini-Medical School course into a graduate program, and joined forces with physiology professor Aviad Haramati, whose experience as a medical educator would be instrumental to securing the grant and to the success of the program.

Haramati and Amri’s grant application was successful, and the Georgetown M.S. in Complementary and Alternative Medicine was born, first as a concentration in the Physiology Program and later as a standalone program in the biochemistry department. Its first class graduated in 2004.

Evolving Experience

Since its inception, the program has grown to train researchers who could “really look into the molecular mechanisms” underlying integrative medicine practices. But students came to the program with a wide range of professional interests in addition to research – particularly in clinical practice. So, over time, the curriculum was expanded to meet the needs of students interested in clinical and other professions.

IMHS alumni and faculty pose together.

“We added courses based on the interests of this young generation,” Amri said. “There is more interest in nutrition, anxiety and trauma, lifestyle and whole health and more, so we developed new courses and added content to existing courses. There is more interest in global medical systems like [Indian] Ayurveda, traditional Chinese medicine, Mediterranean Unani medicine, so we added some content in these areas that wasn’t included in the early years. We added more nutrition, because there is rapidly growing interest in diets, especially diets from different regions of the world.”

She also noted that many students “want to know more about policy, they want to know more about regulation in health care, so we have an elective on regulatory and legal issues surrounding integrative medicine. I have students who want to go to law school specifically to focus on health care law.”

The diverse subjects of the program benefit medical-bound students as well, Haramati noted, by teaching them to think critically about treatment options.

“This is one of the few programs I’m aware of in which we’re not teaching students to think a certain way,” he said. “We’re not teaching them belief – we’re not saying that yoga is better than physical therapy. … We’re exposing you to areas of health and health care that you may not encounter in medical school, and we want you to be aware of it, and we want you to also make up your own mind about what you’re hearing.”

Many medical students are also inspired to create or lead integrative or mind-body medicine interest groups, sharing their knowledge with peers.

The Complementary and Alternative Medicine name would eventually evolve, reflecting changes in the field and the program’s philosophy. The new title, Integrative Medicine & Health Sciences, was approved just before the COVID-19 lockdown in March 2020.

“‘Alternative’ wasn’t really the adequate or appropriate name for it anymore, because we don’t consider traditional practices to be alternatives to our medicine,” Amri said. “They add to, that is complement, conventional medical practices in the U.S. and the West. It’s about making it all one medicine. … In the end, the focus of everyone is to make the patient healthier and feel better.”

A student steps up to receive a superlative award.

Twenty years on, the program is still one-of-a-kind, emphasizing the need for evidence-based validation of integrative medicine practices, exposing the students to specific disciplines within the field, and imparting critical thinking skills that enable students to apply what they’ve learned to their professional practices.

“With the knowledge and perspective gained in our program, they go to medical schools or to the next level of their education with a strong background in this field. And wherever they go in their careers, what they have learned will enable them to apply the principles of whole person health to the treatment of their patients,” Amri said. “That’s what’s really rewarding for the faculty.”

Berkson wrote: “IMHS has been responsible for my academic and professional life and goals. It’s been the cornerstone to my career. … Doors have opened for me as a result of doing the IMHS graduate program at Georgetown.”

From left: Dr. Amri speaks with alumnae Rebecca Berkson (’07) and Rachel Massalee (’19).

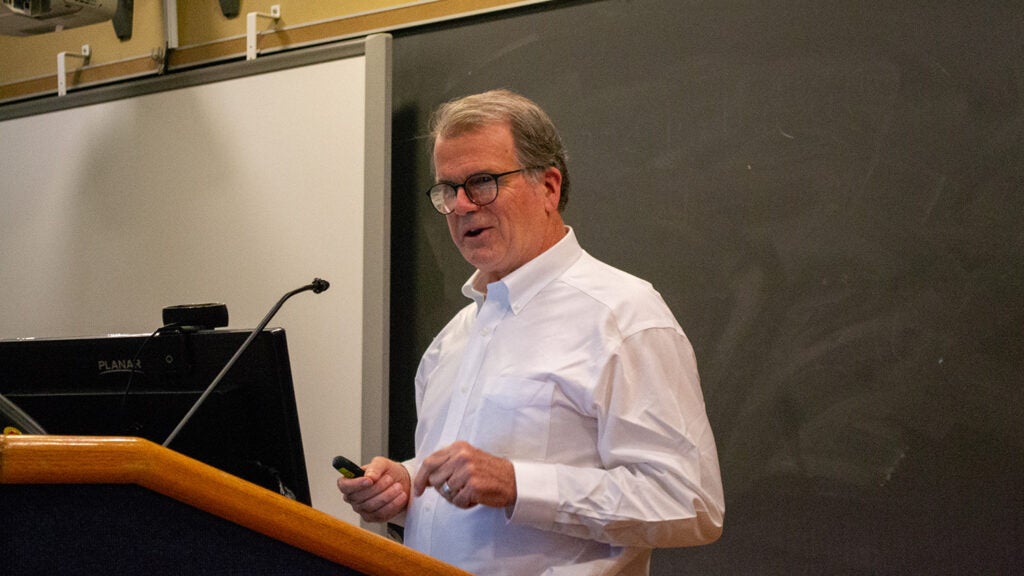

Oncologist Jonathan Stegall (’05) addresses attendees.

Architect Chris Hubbard (’16) gives a speech.

A student walks through the crowd to receive a superlative award.

Class of 2024 students pose with Dr. Amri (left end) and Dr. Haramati (right end).